“It’s never going to be easy.” In capital, the struggle for improved zoning, a better city

By Lucas Cooperman

PANAMA CITY, Panama – Views of Panama City’s shining, vast skyline set on the backdrop of the Pacific Ocean represent the country’s economic development and progress in the past 25 years.

But juxtaposed with the sprawling downtown skyscrapers is architectural evidence of the city’s identity as a collision of international investments and local culture struggling to find solid economic ground.

While at the street level, local Panamanians say they are proud of the diversity across their varied horizon of metal, glass and stucco, architects and city planners worry that the lack of a cohesive long-view master plan has created a scenario of income disparity, environmental inefficiency and a housing deficit that will plague the city for decades to come.

“It’s never going to be easy to solve this situation. The first thing we need to do is to start a strategic housing policy that says what we can do and what we cannot do,” said Rodrigo Guardia, a professor of architecture at the University of Panama. “It needs to be very well thought-out in terms of different considerations, as an important first step. Second, we need to revise local plans and see what we need to keep … and what we need to do to remove.”

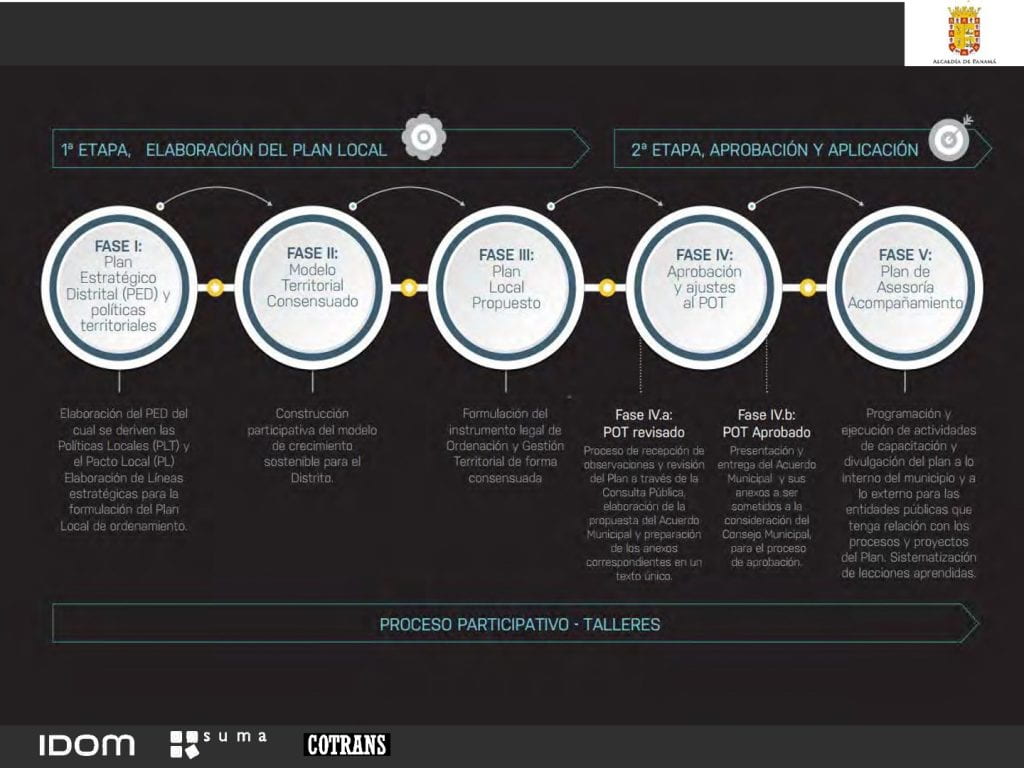

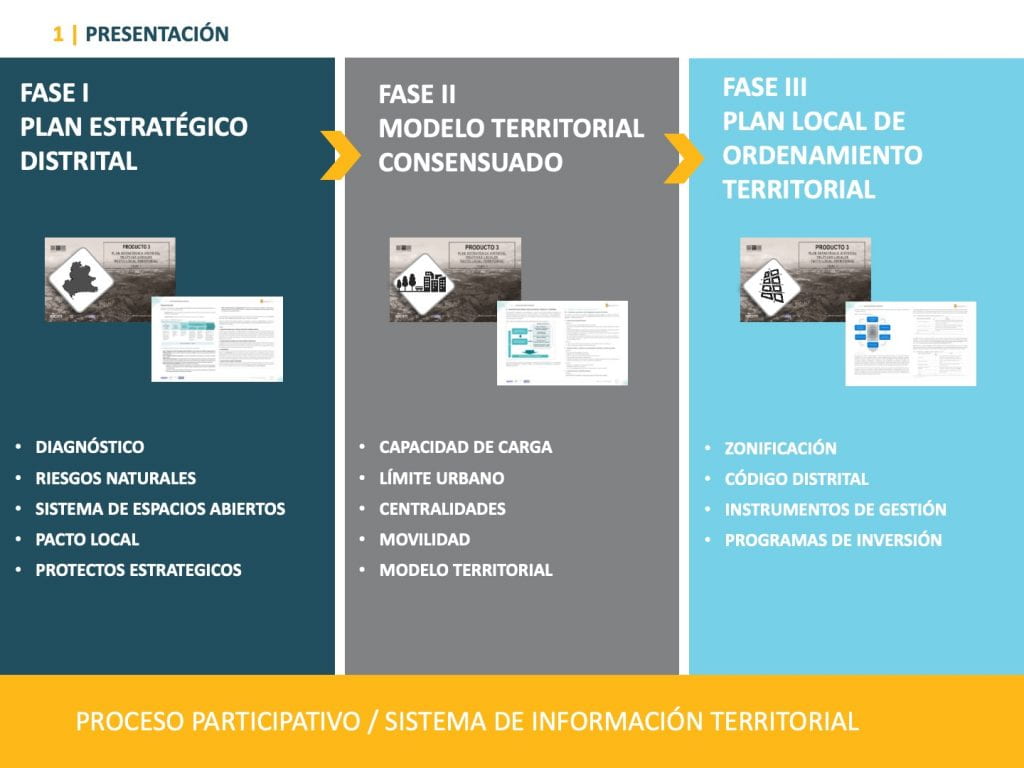

City officials tried to address these issues five years ago by creating a zoning plan for the district known as the “Plan Distrital de Panamá,” but that was abandoned when Mayor José Blandón left the position to run for president, said Raisa Banfield, an architect, sustainability activist and vice mayor from 2014 to 2019.

“The culture of the government over the years is receiving proposals and accepting them,” explained Banfield, emphasizing that without a plan, development goes unchecked. “We say ‘please please, come and do whatever you want.’ I think that Panama is for sale… If you have money, you can acquire land and develop a project as you want, and the people in the city lose.”

The historical lack of a successful and enduring zoning plan has given some experts reason to doubt that such foresight for the whole district is possible.

“I would completely rule out the idea of a unified [zoning] plan,” explained Guardia, who also served as director of research at the Ministry of Housing and Planning from 2010 to 2015. “There have been different plans, but in my experience, these plans are not successful and do not seem like they will be successful in the future. There is not a functional normative framework to protect the interests of the final users of architecture.”

Today, while there is no district-wide official administrative strategy to address these issues, a younger generation of professionals is starting to rumble about what to do – about affordable housing, new sustainable office buildings and energy efficient infrastructure. And if their strategic planning comes to fruition, they hope to create an equitable Panama City with more intentional, sustainable design.

“Rapid unsustainable development is a terrible loss for us, and a problem globally,” said Miguel Espino, lead architect at SUMA Arquitectos in Panama City and a Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED)-certified designer. “As people value more vernacular architecture” – structures built with materials and design elements that reflect the context, climate and conditions of a specific place – “it’s interesting to see how these modern buildings will be rethought. I think the new generation is very much involved in bringing back that identity and sustainability in architecture.”

Nowhere is the jigsaw of architecture and related social issues more evident than in the colorful plazas of Casco Viejo, Espino pointed out. For example: A 360-degree spin around the Plaza de la Independencia highlights the historic Baroque-style Catedral Metropolitana, which is adjacent to terra cotta-topped Spanish colonial houses. Next to that, the structures reflect a French influence with the Hotel Centràl, open since 1874, and the mansard roofs of what is now the Panama Canal Museum. Then, right next to that, the neoclassical columns of the Municipal Palace represent a style of architecture fashionable in 1920s Panama.

“We are a very cosmopolitan people, and very diverse ethnically in terms of national origin,” explained Guardia. “All of this is found in historic districts – buildings built when Panama was a department of Colombia, some during the French canal attempt and some buildings becoming progressively more ornate as there was more of a boom. The canal was a big boom. When you walk around the historic district, you can even see rod iron gates imported from New Orleans.”

But what is there today is vastly different from the scene just two decades ago, when gangs ruled Casco Viejo and most if not all of the historic buildings were in disrepair. The 1997 designation by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization of Casco as a World Heritage Site helped turn government attention on the district. Then the Panamanian government enacted a law in that same year, establishing architectural guidelines and expanding economic protections. And then in 2004, a conservation handbook was established, creating specific recommendations for architectural interventions and new construction, ensuring that renovations in Casco remain true to the district’s historical past.

But the same thoughtful consideration has not been applied to most other areas of the city. Lack of a central, unified plan for development has created a disconnect between the housing and economic needs of the population, experts say. Furthermore, over-zealous development by the construction sector is neglecting low-income Panamanians.

“We have made zoning that has allowed us to build more apartments than we need, more commercial spaces than we need and more offices than we need,” said Guardia, worrying aloud that over-development not only disadvantages poorer citizens but in fact marginalizes them from what they need most: a safe, affordable place to live.

Today, roughly 40% of metropolitan housing in Panama City has been developed under what experts call “informal conditions,” or when housing is built with improvised materials, without secure tenure of land and without conforming to building codes, construction standards and compliance checks, experts maintain. As a result, outside investors and developers reap the financial rewards while the people who dwell there pay the price.

A recent technical report found that nearly half of households in the metropolitan area cannot afford even the least expensive housing produced in Panama City’s recent building boom. That means for residents living in the thousands of substandard housing units inside Panama City but just outside of Casco Viejo, they have no hope of moving into newer, safer units because the prices are far out of reach.

“This is a structural economic problem that leads to a huge deficit between high-income and low-income housing,” explained George Kourany, an architect, urban planner and professor at the University of Panama since 1972. “This is expressed by where people and their families live. Many [Panamanians] are settling in houses of wood between the high-rises, not in them.”

Kourany suggested a solution to the housing problem: developing better designs. Adapting new housing structures to the tropical environment of the city is key, as well as investing in infrastructure and architecture around the outskirts of the city. “You don’t have to go to 100 levels to be happy,” he explained.

Despite such cautions voiced by experts, not everyone believes that booming development and an increasing number of skyscrapers are harmful. Rather, some residents and employees of the capital express pride at a glittering landscape and say they view it as an indication that they inhabit a world-class city full of money and prestige.

“Skyscrapers make the city seem bigger and more modern,” said Maximo Moráles, who works as a valet in Casco Viejo and lives near the Tocumen International Airport, about 35 minutes outside of its epicenter. “The skyscrapers aren’t a bad thing. They look nice, they are very beautiful. Other areas look run down, so there is a big contrast there, but I like it.”

Others see the development in the city as just another iteration of the country’s storied history as a blend of foreign influence and money.

“Panama has always been a place of transit,” said Luis Meléndez, a Panama City tour guide who lives on the border of tourist-friendly Casco Viejo and the historic yet embattled El Churrillo neighborhood, which U.S. forces bombed in 1989 to overtake former dictator Manuel Noriega. “Since the time of the Spaniards, we have always had foreign influence and different trains of architecture… New global trends in architecture have always been implemented here, changing the landscape, but it has always been a city that is constantly changing.”

Meléndez explained that while a boom in high-end construction in the 2000s created many jobs for low-income workers, it also created a real-estate bubble, and housing prices went up. But to many Panamanians, the implications of the rapid construction are less important than the quick economic boost construction jobs create, said Banfield.

“After God, nobody can touch [construction in Panama City] because it produces a lot for the gross domestic product,” explained Banfield. “The construction sector creates employees, and there is excitement about the skyline and looking like other cities.”

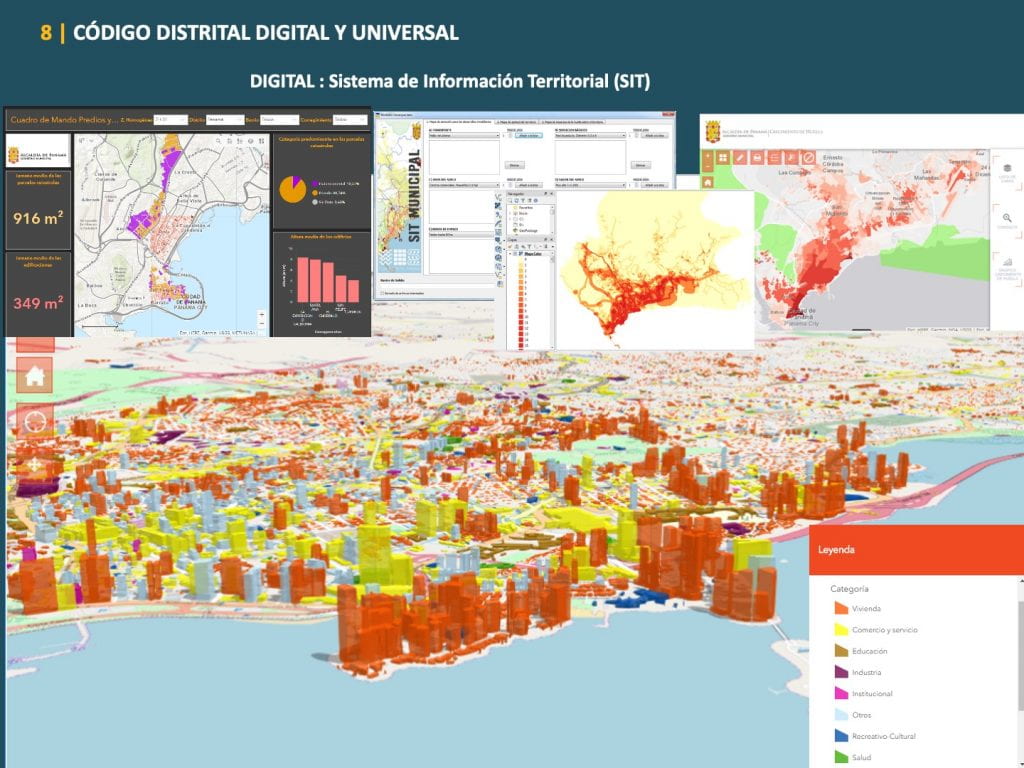

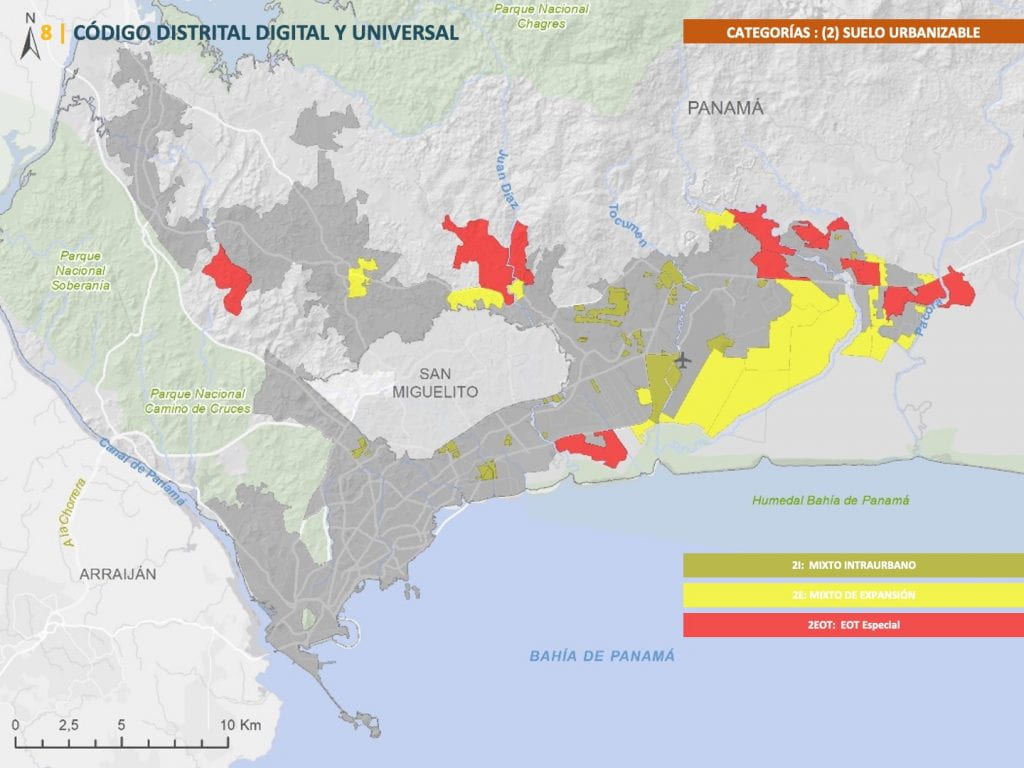

According to experts, the biggest problem with zoning and planning in Panama City is that the reality of development is disconnected from the actual housing needs of the population. While the ambitious Plan Distrital de Panamá ended up flopping with the change in the city’s mayor, as Espino explained, the plan and others like it represent a significant crossroads for the city.

“This is a turning point in our history,” said Espino. “It marks the beginning of Panamanians worrying about [the sprawling development] in the city.”

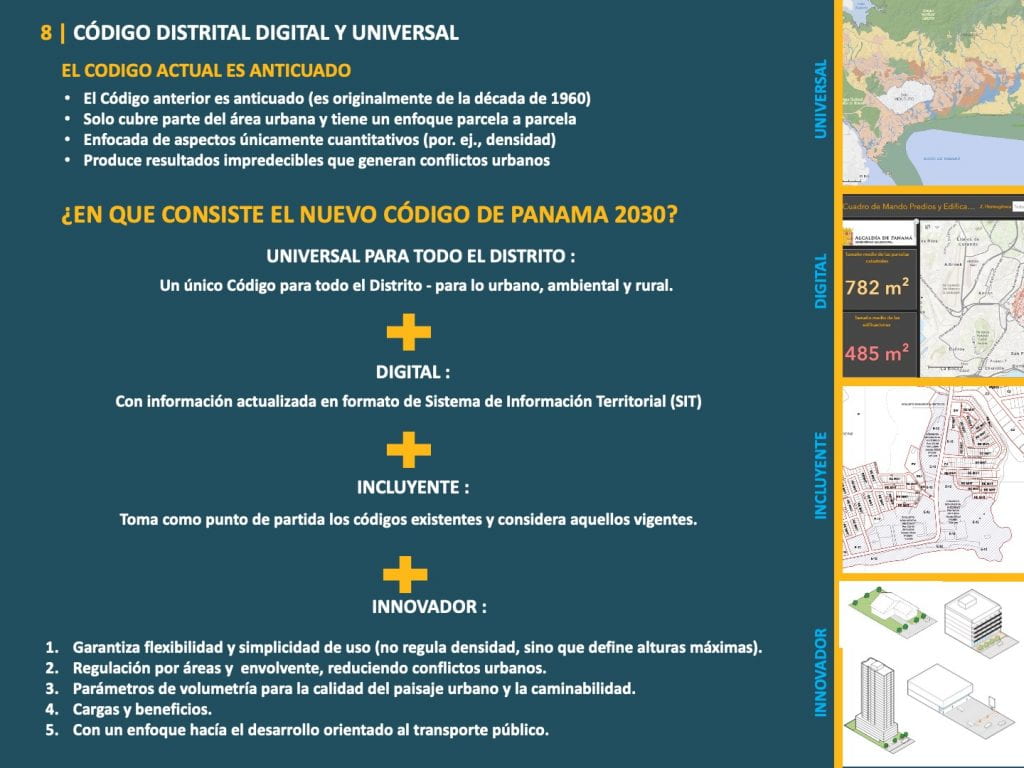

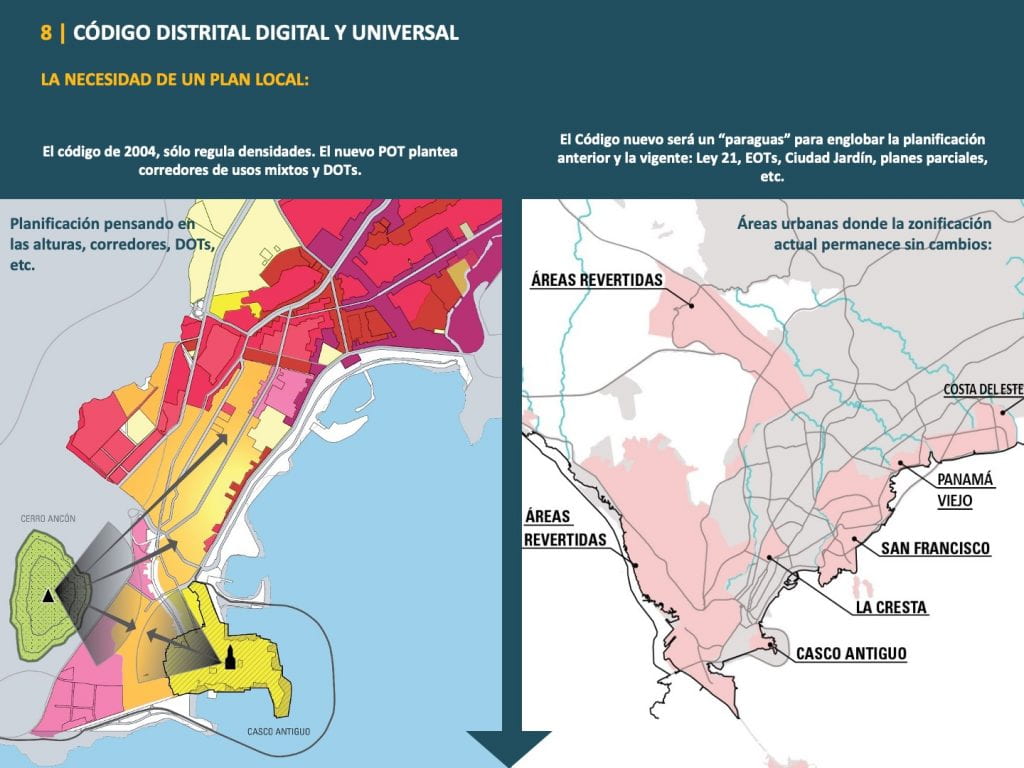

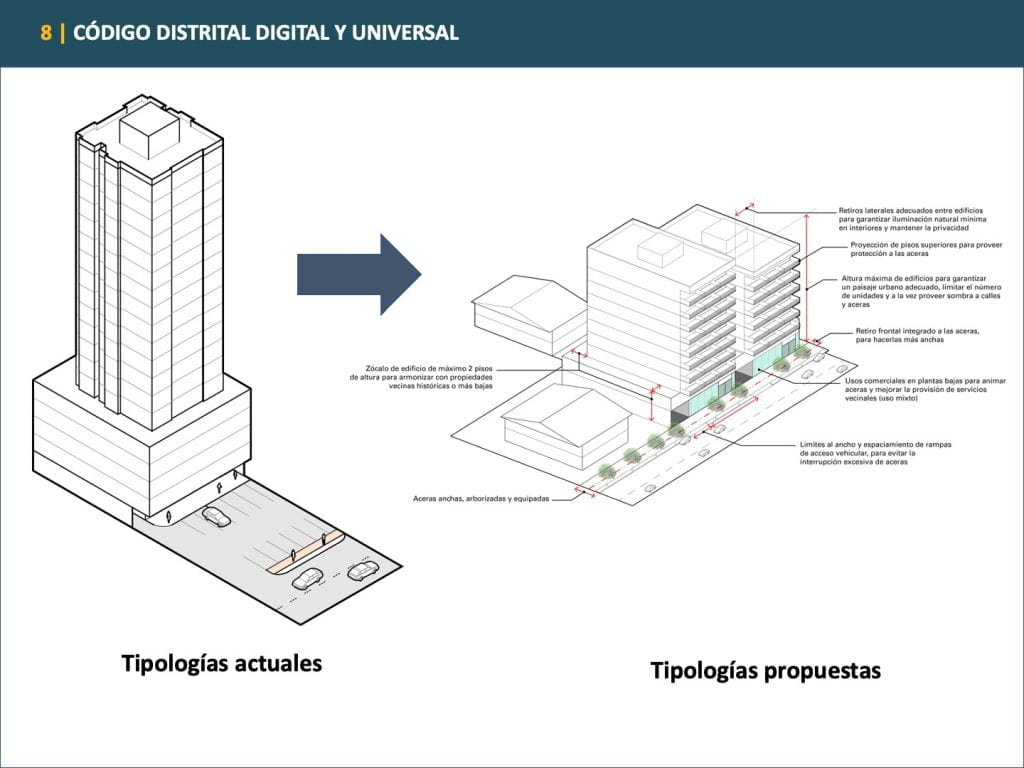

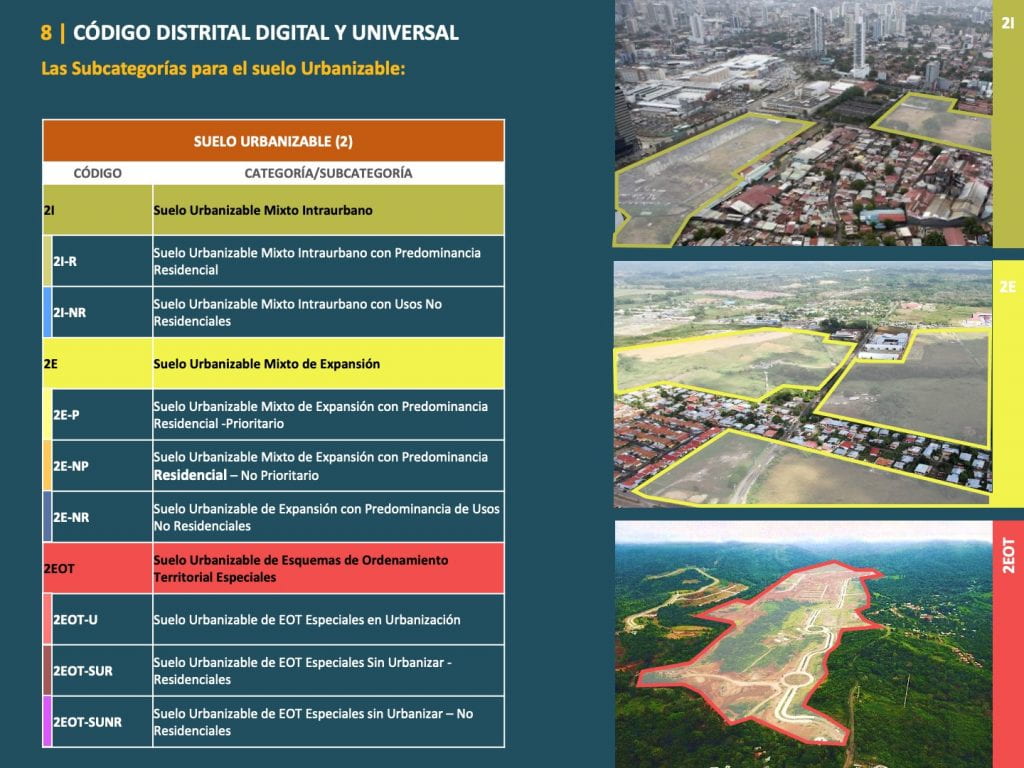

The proposed Plan Distrital de Panamá states that current zoning codes, originally created in the 1960s, are outdated. According to Guardia, height restrictions on buildings were codified until the military government of the early 1970s eliminated such restrictions and incentivized densely populated developments. The Plan Distrital states that as a result, this type of zoning has produced “unpredictable results that generate urban conflicts.”

“The zoning and the incentives are not effectively providing the type of housing that is required by the unmet demand,” explained Guardia. “This has to do with income, but it has more to do with the absence of public policy.”

The lack of public policy has allowed for the creation of high rises that are not made to meet the demands of Panama’s humid tropical climate, said Espino. For example, skyscrapers in the city are largely built using glass, and pose a detriment to the environment.

“In this climate, glass is inoperable,” explained Espino. “These buildings don’t respond to their environment, and energy costs go way up. It’s nice to have natural cooling and to be connected to the environment, but people don’t want to be uncomfortable with their environment, which has big implications for energy costs… Policies need to be put in place to incentivize green architecture.”

One example of green architecture can be found throughout the modernist El Cangrejo neighborhood on the west side of the city. According to both Espino and Guardia, this area is environmentally “sound,” and its walkability is something the rest of the city should aspire to.

“I really like El Cangrejo, both because of its modernist style and its sensitivity towards climate,” said Espino. “The depths of the facades on many of the buildings work great with the environment [to help with natural cooling]. The area gives a lot of importance to balconies, sidewalks and each street’s blocks. It is well developed, with a lot of great architecture.”

As for the future of Panama City’s zoning plans and landscape, opinions vary among experts.

“I am not optimistic, but I am hopeful,” said Guardia. “I feel frustrated, it’s often infuriating… other urban planners and I feel like we can see these problems very clearly, but we cannot manage to take control of the situation. We know this, and we are not able to enact actual change.”

But the very presence of a zoning plan like the Plan Distrital de Panamá is enough to convince Espino that Panama City is moving in a positive direction.

“These trends will continue, because the plans were made with community involvement,” he explained. “The government is asking people what they like, what they need, what the priorities are. It is very hard to go back from that now. We can only move forward,” he said. “There is always friction when something new is proposed but that’s good because we are getting a chance to say what is important to us.”