Tourism funding ushers in waves of development in Casco Viejo

By Zoë Bleu Sommers

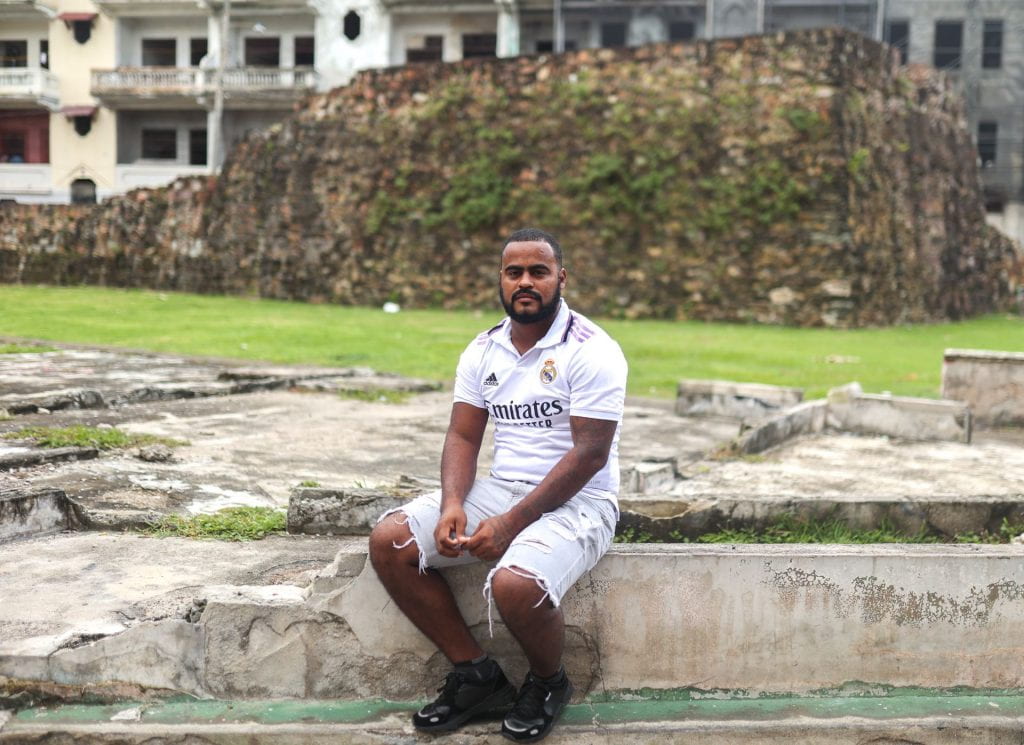

CASCO VIEJO, Panama – “Our community is being displaced,” said 24-year-old Cristian De La Rosa in an interview translated from his native language, Spanish. “We have investors coming in and buying these buildings, and the prices go up.”

De La Rosa is a native to Casco Viejo. He was born and raised just down the road. He lives on 11th Street now. He’s been here his whole life, but worries that the impact of tourism investment will make it harder for him to stay.

Tax incentives and zealous timeline goals for increasing tourism to Casco Viejo are inspiring rapid development for high-end accommodations and offerings for tourists. While laws decreeing these initiatives were put into place a decade ago, recent years have brought in more revisions that businesses can take advantage of now that Covid restrictions are loosening.

Just about half of the buildings in Casco Viejo, also known as Casco Antiguo or San Felipe, sit in disrepair, many filled with trees and creatures that rival the biodiversity of the jungle just outside of the city. The remaining buildings are renovated with such attention to detail that a stroll down one of the district’s 15 streets is like a step into the past.

This is the Casco Viejo that the Panamanian government is trying to preserve – and promote. One initiative that’s already been completed is the nearby Amador Cruise Terminal. With its opening in November comes an opportunity to draw in docked cruise ship passengers and increase the number of tourists to Casco Viejo, a subsection of Panama City that juts out into the ocean. The neighborhood’s location was chosen in 1673 to safeguard against opportunistic pirates.

According to Fernando Díaz Jaramillo, director of the Office of Casco Viejo’s Ministry of Culture, the port’s opening is just the beginning of opportunities to pull in high-spending tourists.

By pouring millions of dollars into the small neighborhood, designated in 1997 as a World Heritage site by UNESCO, officials are trying to make what they call the “tourism destination argument.”

As the “oldest continuously occupied European settlement in the Pacific coast of the Americas,” this area warrants the attention. According to the World Heritage Convention, there are three main reasons why Casco Viejo bears enough cultural significance to warrant its multiple historic designations, some of which date back to 1976: It shows exemplary design in town planning; it represents an exceptional part of Spanish colonial culture; and it is strongly linked to European discovery and infiltration of Central America.

Right now, the Panamanian government is in a race to restore the rest of Casco Viejo so it can meet ambitious goals for the development of tourism, including “to be recognized as a world-class sustainable tourist destination, thanks to the extraordinary richness and diversity of its natural and cultural heritage and the quality of its services,” according to the Tourism Authority of Panama’s “Master Plan of Sustainable Tourism for 2020-2025.”

Part of the infrastructural changes planned include a return to the bygone days of car-free streets.

First, all of Avenida Central – the main street though the neighborhood – will be pedestrianized, meaning all car traffic will cease. The goal is that the rest of Casco will follow soon thereafter. There will also be new electric buses by April 2023 and trolleys for tourists. Partnerships with companies that rent out electric carriages and scooters are also in the works.

In order to support these changes, Jaramillo said that larger-capacity parking garages and a solar panel facility that can support the anticipated additional electricity consumption will be constructed on the outskirts of the city. With only about a year and a half left until the deadline, it’s an incredibly ambitious plan.

But for the Ministry of Culture, expansion is necessary to drive home the tourism destination argument: “We are now presenting to UNESCO a new candidacy of the World Heritage site,” said Jaramillo. Expanding the site’s boundaries would impose its strict rules for maintenance on a part of the city that houses even more locals.

“We are [trying to add] the two colonial roads to the classification: Camino Real and Camino de Cruces,” he said. “It’s all going to be a part of this big serial UNESCO site.” These roads were the original transisthmian passages that connected the Caribbean Sea with the Pacific Ocean, so they do bear a significant historical value. Camino de Cruces led travelers from Casco Viejo to the head of the Chagres River, near what is now Colón, while Camino Real led to the seaside fort-town Portobelo.

Their addition to the UNESCO site is sensible; by including more areas with historic value to the designated site, more opportunities to capitalize on tourism arise.

According to Jaramillo, this expansion provides a chance to improve the livelihoods of many who live in the area. “We have a vulnerable population of 500,000 people that could profit from what we’ve done here.”

Experts hope that one of the results in expanding the tourism industry is more job opportunities for locals. Alicia Jiménez is a professor of economics at University of Panama business owner and the president of the national Chamber of Commerce organization in Panama.

“We do need to develop tourism,” Jiménez said. “Right now it represents just 4% of [the country’s] GDP.” Increasing this percentage is particularly important to her because doing so means a lower unemployment rate and job opportunities for Panamanians. First, more buildings need to be put into use.

Within the boundaries of the quaint neighborhood, there are just under 1,000 lots. Of those, more than 90% are privately owned. Per the World Heritage requirements from UNESCO, private owners must use architects that specialize in restoration for any renovations that take place.

Daniel Young-Torquemado is a Panamanian architect who meets these qualifications. He finished school and began his career in the neighborhood shortly after its World Heritage inscription, in 1999.

“Before the UNESCO label, there wasn’t much happening in Casco,” he said. “It wasn’t even on our radars.” At that time, Casco Viejo was infamous for being on the dangerous side of town. Indeed, until the mid-to-late ‘90s, the neighborhood was most known for its crumbling buildings and the gangs that occupied them. For many, escorts were required to even pass through.

The World Heritage designation put into place certain protections and incentives for renovating the area. According to Young-Torquemada, there are several steps that must be taken before ground is ever broken. These steps culminate to a roughly two-year process.

First, architects must do intensive research into the history of the building. Then, they must bring in an archaeologist to verify the various phases of occupation throughout the building. Only after this can they begin the new design plans for the restoration and hope for approval. The finished result should be a completely updated interior and a replicated or preserved exterior.

Central to this process is “understanding the attributes that convey the building’s [historical] significance,” said Young-Torquemada. This preservation of culture embodies perfectly what tourists are looking for: the “authentic” Panama experience. It should also be noted that this authenticity comes at a price. Young-Torquemada says that the average construction costs for restoration are between $1.5 million and $2 million, in addition to the initial cost of the property.

With the average price-per-square-foot having nearly tripled since Young-Torquemada began his career, jumping from less than $100 in 1999 to over $350 now, there’s no doubt that completely restoring Casco Viejo is going to come with a big price tag.

Because of this, the pool of eligible buyers and renovators has continually diminished.

To combat this, Jiménez, who was also the vice minister of housing in Panama from 1999 to 2004, championed a low-income housing project for locals during her tenure. In her opinion, ensuring that locals have the opportunity to stay in Casco is a key way to protect the culture of the neighborhood that attracts visitors in the first place.

Nicola Ashdown and Pam Jardine traveled to Panama as a part of a British and Irish tour group whose trip originated in Costa Rica. Their main destination in Panama was a six-hour ride down the canal, but Ashdown said that she was smitten with the historic area of the city. “You get a proper feel of Panama in Casco Viejo,” she said.

The pair stayed in the skyscraper side of Panama City during their stay, but both were disappointed with their experiences there. “There are no artisan shops or anything in the new part of the city,” said Jardine. Not to mention, the view of the skyscrapers is better in Casco.

Both women said that if their trip organizers had booked them into hotels in Casco Viejo, they would have been spending money at the local-feeling shops and restaurants there.

Spending money in Casco Viejo seems to be exactly what the tourists want to do. Jana and Mary Hart, a mother-daughter duo from the United States, visited Panama on a weekend trip.

The elder Hart, Jana, was impressed with Casco Viejo. “It feels safe and very hospitable,” she said.

The younger Hart said that if there were more boutiques, she would have been inclined to spend liberally. She said she would have loved to support as many local businesses in the area as possible.

The comfortable nature of Casco Viejo is one of the reasons officials think it’s a perfect tourist destination. In this rush to accommodate and attract more tourists, one hotel in particular is garnering loads of attention; it’s hard to go even a full day without hearing of the newly opened Hotel La Compañía.

Part of the luxury Unbound Hyatt line, the hotel comprises three buildings, each of which has distinct historical significance. The hotel’s starting price is just under $350 per night, expensive by Panama standards. Inside, there are five upscale dining options. Across the street sits the luxury skincare store, Orogold, where employees say 95% of business comes from tourists.

It wouldn’t be surprising if even more hotels start popping up in Casco Viejo now that Covid restrictions around the world have started to loosen. In late 2019, the federal government voted to install a 100% income tax credit for investments made by tourism companies formally registered in the National Tourism Registry. The country-wide incentive was signed into law in 2020 by Panamanian president, Laurentino Cortizo Cohen.

Incentives such as this make it far easier to set roots as a business than as a resident. Estimated census numbers further illustrate that divide: Jaramillo said that in 1990, there were about 10,000 residents in the neighborhood. This year, his office believes that number is down to around 3,000.

Gabriela Loré works at the front desk of Hotel La Compañía. She doesn’t know anyone who lives in Casco Viejo, though she herself would love to – if she could afford it. “As a Panamanian girl, I don’t know Casco Viejo places,” she said. “I know they exist, but I don’t enter.”

Her biggest hope for the development of the neighborhood is that it becomes more accessible to locals. “Casco is a really inaccessible place,” she said. “I think it should also be for local people – they need to experience things too.”

Jaramillo acknowledged that a formal plan is necessary to limit the number of hotels, bars and restaurants that can be built in the neighborhood in order to preserve some of the culture that actual residents would contribute. Additionally, he noted that there are several upcoming plans for more social housing to be constructed for residents in the area.

For many of the neighborhood’s current residents, living in Casco Viejo seems to be getting harder. De La Rosa says that he’s not sure he’ll be able to stay in the place where he grew up if the government keeps pushing for tourism development in the way it’s been doing.

“All our life, we’ve lived here, we’ve grown up here. It wouldn’t be easy for us to live in a different area,” he said. “[But] Casco isn’t ours anymore.”