TV Indígena: The story of how one small station helps keep indigenous culture alive

By Kenneal Patterson

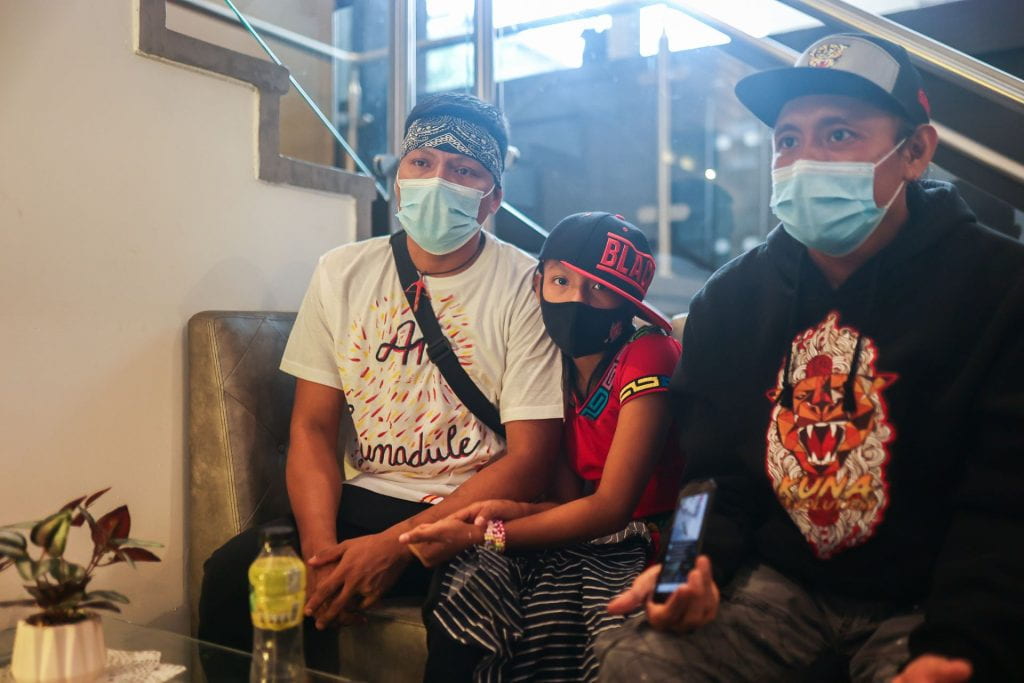

PANAMA CITY, Panama —Huddled under the fluorescent lights of Panama’s City’s Teatro Municipal Gladys Vidal, Juan Carlo Gonzalez sat with his arm wrapped around his young daughter. They had a few minutes left together: soon, they’d enter the auditorium where Gonzalez, a.k.a. “Rap Sabdur,” and his collaborators would introduce their music video during a showcase for his indigenous Guna tribe.

Exhausted, the 9-year-old little girl slumped against Gonzalez, her “Mola”-patterned tribal dress washing the white room with pinks and yellows. He, too, wore a traditional sign of his people: a carved pendulum in the shape of a medicinal vine.

Other than nods to their native roots, the pair looked like a modern-day father-daughter duo. In fact, both brazenly bore signs of the new millennium: the daughter with a wide-brimmed snapback cap, the father with a white t-shirt and black bandana headband. Together, they epitomized many 21st century Gunas: one foot in their Gunayala community, one foot in westernized hubs like Panama City.

This cultural revolution is taking place thanks to broadcasts like TV Indígena, which provides a platform for creators like Sabdur. The station, which livestreams traditional Guna elders on social media platforms like Instagram and Facebook, has accumulated over 50,000 followers since its creation in 2017. Like Sabdur, many Gunas hope to teach young city-dwellers of their traditional customs, and modern technology has given them the ideal opportunity.

Sabdur has been in the music business for over 15 years, joined by other collaborators like Sarky Real and Sidsagi Inatoy of rap group Kuna Revolution. They upload videos on their own platforms but are further supported by friends at larger networks like TV Indígena, which can transmit messages to Gunas around the world, a population estimated at 95,000. So rather than crooning about lost love, these rappers are spitting bars about protecting Mother Earth and preserving Guna knowledge.

“I was once a young kid losing my identity, thinking of getting a car and getting work,” Sabdur said in an interview translated from Spanish. “Then, my daughter started asking questions about our culture I couldn’t answer.”

Over 62,000 Gunas today are living on the tropical islands off Panama’s northeastern coast and along about 185 miles of coastland. Their four main autonomous territories in the country are known as Dagargunyala, Madugandí, Wargandi and Gunayala, the largest. There, for hundreds of years, they’ve made the Caribbean waters and palm-strewn archipelago their home. This oceanic haven sheltered them from murky jungle diseases, often mosquito-borne, and provided them with easy access to coastal trade industries, such as coconut and turtle shell. Due to an influx of industrialization, however, many young Gunas are departing the shoreline and forgetting their cultural past. Stories are lost as families move to global metropolises. Guna history, passed down through spoken word, rarely reaches urbanites living hours away.

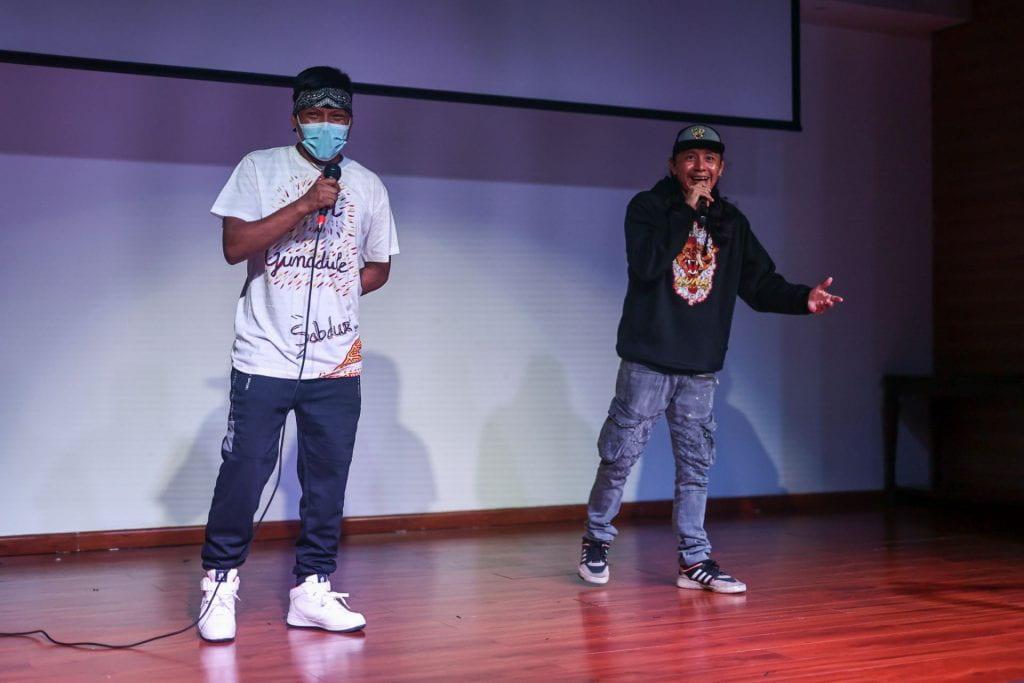

There was a hush in the audience as Sidsagi and Sabdur took to the stage. Then, one by one, people raised their phones. The devices emitted dim light as the audience began to record. Seated in the front row, TV Indígena’s Iniquilipi Chiari balanced two phones on top of one another – the first recording, the other streaming the station’s Instagram Live. Any Gunas with internet access could tune in and honor their heritage.

As Sidsagi introduced the music video with his partner, a lone jaguar tooth dangled around his neck. He later noted that the creature died of natural causes and was blessed by a traditional Guna shaman. It stood in stark contrast with his ripped skinny jeans, gray hoodie and ability to rap a song that could easily be on a Billboard chart. But Sidsagi’s not after fame.

“Making our music is really fulfilling,” said Sidsagi. “It’s better than winning a Grammy. You’re contributing to saving lives.”

Their song, “Nabgwana,” encapsulates their commitment to environmental activism. Gunas are deeply connected to nature: when a child is born, the placenta is buried under a newly sprouted tree, forever intertwining that life with the Earth. The song deeply moved Iniquilipi, who also serves as the head of the office for the Environment of Indigenous Peoples at the Ministry of Environment of Panama.

“I’m thinking about my community and thinking about the past,” he said. “But also, of the new generation.”

***

Chiari and Olo Villalaz founded TV Indígena five years ago with this younger generation in mind. In the beginning, it was just a dream: two political advocates hoping to launch their own streaming business with only their salaries to fund the endeavor. But they stayed true to their mission: helping their indigenous brothers and sisters showcase their culture. Before long, TV Indígena grew.

“Indigenous people from different territories, from different nations, could come and join us,” said Chiari in an interview in May.

A couple of days before the Auditorio Gladys Vidal performance, Iniquilipi and Villalaz visited the old part of Panama City, Casco Viejo, to talk about the evolution of their station. Villalaz wore a traditional Guna necklace given to him by an elder he interviewed during the pandemic. Throughout the quarantine, the elder couldn’t teach, but Villalaz’s virtual platform gave him new hope.

A connection with Guna elders was the foundation of TV Indígena. “For a lot of indigenous people’s culture, it is not easy to be open about our spiritual beliefs,” said Iniquilipi. “That’s why it’s all about trust.”

It’s taken them years to build up this trust. Guna people have suffered at the hands of the Western world: enduring colonization, modernization and globalization that effectively forced their people into a mass exodus to the country’s margins. Spanish conquest destroyed their home, and years later, oppressive Panamanian rule sought to eliminate their culture. Fed up, Gunas revolted in 1925 during the “Dule Revolution” and managed to gain control over their land.

But this autonomy only protects them so much. Today, the Guna people still face threats of cultural extinction. Even if they resist assimilation, they must cope with the dangers of a warming world. Sea levels are rising, and before long, their island homes could become submerged, forcing them into barracks-style housing provided by the government but not representative of their culture and traditions.

Chiari and Villalaz knew the situation was dire, and in 2017, TV Indígena was born. The follower count skyrocketed in 2020 during the pandemic, when the station kept track of statistics that even the government didn’t have. In May, during the height of the crisis, the station had already recorded 430 cases and 20 deaths, and was regularly posting health recommendations on all their social networks.

Two years later, they’re still connected to loyal followers, but they’ve also enlarged their audience. The station goes live every night from 7 p.m. to 9 p.m.: broadcasting community happenings, indigenous world news, an array of Guna-created music and even sports. They don’t have a channel or a space on the airwaves, but they make do with their devices. TV Indígena has brought in followers from as far north as the Netherlands and as far east as Taiwan. Sometimes, the videos are only streamed in the Guna mother tongue to safeguard confidential information. But it’s regularly streamed in Spanish as well. Without Chiari and Villalaz’s dedication, thousands would never know about the Gunas’ existence.

Activists across Panama do what they can to prevent these communities from vanishing. Cultural outposts like the Mola Museum, a textile-filled history museum in the heart of Casca Viejo, even attempt to preserve Guna handiwork, but on May 20, a Thursday in the tourist-swarming Casca Viejo district, the building’s halls were empty. Colorful, intricate Molas adorned the walls, but nobody was there to see them.

“I’ve been living in Panama my whole life but the first time I started learning about [Molas] was when I was working here,” said Vianca Monterro, the museum’s 26-year-old assistant director.

Monterro’s story is typical, she said. Many Panamanian classrooms gloss over curriculum regarding indigenous ways of life. During time at public school, she remembers these communities being carelessly grouped together or dismissed. Other times, they were regarded as remnants of the past – objectified as ancient artifacts rather than as a community with distinct heritages and cultures.

Panamanian visitors enjoy the museum, said Monterro, but on a grander scale, the historical rift between indigenous nations and the Panamanian people still persists. Ignorance is systemic, pervading school systems and government offices. And Guna people are wary of “waga,” or outsiders, for good reason. For years, anthropologists and scientists have pursued the Guna people in attempts to document their practices. Some taped audio recordings of elders in the 1960s and ‘70s, forever preserving their sacred rituals. But Chiari and Villalaz agreed that others viewed the Guna people simply as cultural curiosities, something to gawk at rather than to honor, study and preserve.

But little by little, elders are once again starting to trust technology by speaking up to reclaim their stories.

It works like this: Chiari or Villalaz will settle in at home, where they coordinate the broadcast. They can’t use a studio, and can’t air on any cable channel, but the logistics pose few obstacles. The power of social media is readily available.

For only a few dollars, they’ll purchase a data connection day-pass for a Guna elder. With a little patience, a little luck, and the help of Tigo or Digicel, the livestream begins, and before long the elder is recounting his teachings to thousands of eager listeners.

“It’s just like a jukebox,” joked Villalaz. “You put a coin in, and they won’t stop talking.”

Later, the videos are archived on their page, permanently in cyberspace. This is how they preserve stories for future generations. This is how they safeguard their existence.

Carlos Carpintero, a 31-year-old university student from the Ngäbe Bugle tribe, discovered TV Indígena through Facebook Live. Over 260,000 Ngabe people inhabit Western Panama and parts of Costa Rica; Carlos, however, lives in Panama City. Carpintero deeply believes in the preservation of indigenous culture: today he produces photos, typically soulful portraits, of indigenous people in their natural environment. His most recent portfolio was titled “Guardians of the Earth.” He’s also listened to TV Indígena for years and expressed gratitude at its educational programming.“You can reconnect with the things that we as indigenous people have done throughout time,” he said. “It’s for [both] our ancestors and the kids of the future.”

Carpintero believes there should be even more indigenous TV stations, including those that can dive deeper into the culture of each tribe. Panama has seven distinct indigenous peoples: the Gunas, the Emberá, the Wounaan, the Ngäbe Buglé, the Bri Bri, the Bokota and the Naso Tjerdi. Carpintero is committed to preservation, not just for indigenous communities today, but for the sake of the future generations.

After the interview, Chairi left for a meeting with COONAPIP, the national coordinating body overseeing the indigenous community. In Panama City, he’s both a spokesperson for the Guna community and an advocate for environmental protections, serving as a sturdy bridge between the citizens watching TV Indígena and the politicians that govern them.

Villalaz, on the other hand, will hit the open road: he dreams of hopping on a motorcycle and embarking on a voyage to visit each indigenous nation. At each stop, he’ll chronicle the community’s connection to the natural world. In fact, over 60% of Panama’s rainforest is in indigenous land – land that has been contended for centuries. TV Indígena projects these narratives until people begin to listen.

To Guna people like Chiari and Villalaz, there’s something powerful about streams: from the tributaries encircling their homeland to the swift currents of information spread online. Coursing through a handheld phone screen and a computer monitor, TV Indígena’s revolution goes viral. Their plea – for the rights to land, culture, language and livelihood – surges across cyberspace. As does their promise to native peoples– that their legacy will not be forgotten.

To Chairi, it’s not just a job, it’s his duty. “We have a responsibility for sharing this knowledge with the world.”